- Although the Hill of Tara – 48km northwest of Dublin – stands only 90m above the surrounding countryside, it commands a view over 40% of Ireland (on a clear day). Tara was the seat of the High Kings of Iron Age Ireland from about 500 BC to AD 500, but used in the Stone Age, as shown by the 4500-year-old passage tomb known as the Mound of the Hostages. Kings, poets and heroes came to a great gathering (feis) at Tara every three years to make laws, settle disputes and review the poems and stories that every poet kept in his head.

- One of the great kings of Tara, Cormac mac Airt (3rd century AD), gave a famous judgement when he was only a young boy. Sheep belonging to a woman ate grass in a man’s field, and the man demanded that the sheep be given to him as compensation. The king said that was fair, but Cormac disagreed. He said that since the grass would grow again, a fair payment would be for the woman to give the man the fleece (wool) from the sheep, but keep the sheep – “One shearing for another”. This was the true judgement, and it was incorporated into Irish law.

- In the sixth century, the king's soldiers killed a man who had gone into a church for protection, and St Ruadán cursed Tara – "May Tara be desolate forever". Tara was abandoned and ceased to be the political capital.

- However, it remains the spiritual capital of Ireland. The Battle of Tara during the 1798 Rebellion was more symbolic than strategic. The rebels lost, and some of them are buried under the Forragh. In the 1840s, the great Irish leader Daniel O'Connell called a meeting at Tara to protest against the treatment of Catholics. He stood on a wooden platform especially constructed for the occasion on top of the Mound of the Hostages. Over one million people attended.

- "The Hill of Tara had five names. The first was Druim Decsuin, or the Conspicuous Hill; the second was Liath Druim, or Liath's Hill from a Firbolg chief of that name who was the first to clear it of wood; the third was Druim Cain, or the Beautiful Hill; the fourth was Cathair Crofinn; and the fifth name was Teamair (now Anglicised Tara, from the genitive case Teambrach of the word), a name which it got from being the burial place of Téa, the wife of Eremon, the son of Milesius."

from Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish, by Eugene O'Curry, Dublin, 1873.

The granite Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny) is one of the four treasures brought to Ireland by the magical Tuatha Dé Danann. When the true king stepped on it, it shrieked. This was the voice of the Earth Goddess approving him as her consort. An obvious phallic symbol, it probably originally stood at the entrance to the Mound of the Hostages, a symbol of a pregnant woman’s belly, and was later moved. The stone seems to have been toppled and buried on the north side of the Mound by the time of Conn of the Hundred Battles in the 2nd century AD. Conn and his druids were walking along the “ramparts” – probably the Royal Enclosure – of Tara when he accidentally stepped on the Lia Fáil, which he had never noticed before, and it screamed so loudly it could be heard for miles around.Murtagh, a 6th-century king of Tara, loaned what was obviously a fake to his brother, Fergus, king of Scotland. (Some say it was taken by a group of Irish émigrés when they colonised Western Scotland.) This block of red sandstone eventually became known as the Stone of Scone. The English stole it in 1296 and put it under the throne at Westminster Abbey, calling it the Coronation Stone. In 1950, Scottish nationalists stole it from the English and replaced it with a replica. Then Irish nationalists stole it from the Scottish. The English recovered what may have been yet another fake. Some say it was never taken from Tara at all, but no one in Ireland denies that the stone you see at Tara is the authentic Lia Fáil. On 15 November 1996, and with grand ceremony and expecting fulsome gratitude, the English returned what they think is the Stone of Scone to the Scottish. The bemused Scottish reaction was, "It's about bloody time."

I suspect that when Tara was cursed and abandoned in the 6th century, the Lia Fáil was buried, if it had not already been buried four centuries earlier, and Murtagh’s “loan” of the stone to Fergus was arranged as a red herring so that some upstart might not use it to become king. This fiction was carefully maintained after the Anglo-Norman invasion in the 12th century to conceal the presence of the Lia Fáil from the invaders. By the time the commemorators of the rebels killed in the ill-fated 1798 Battle of Tara dug up the Lia Fáil and planted it on the Forrad in plain sight, even if this made the British aware that they had been tricked, it would have been too embarrassing to admit that their Coronation Stone had been a fake all along.

- The Mound of the Hostages is a 4500-year-old passage tomb and is the location of the story Fionn mac Cumhaill and the Burning of Tara. The passage is aligned to the rising sun on 8 November, the old 1 November, making it an entrance to this world from the Otherworld on the preceding night: Oiche Shamhna – Halloween.

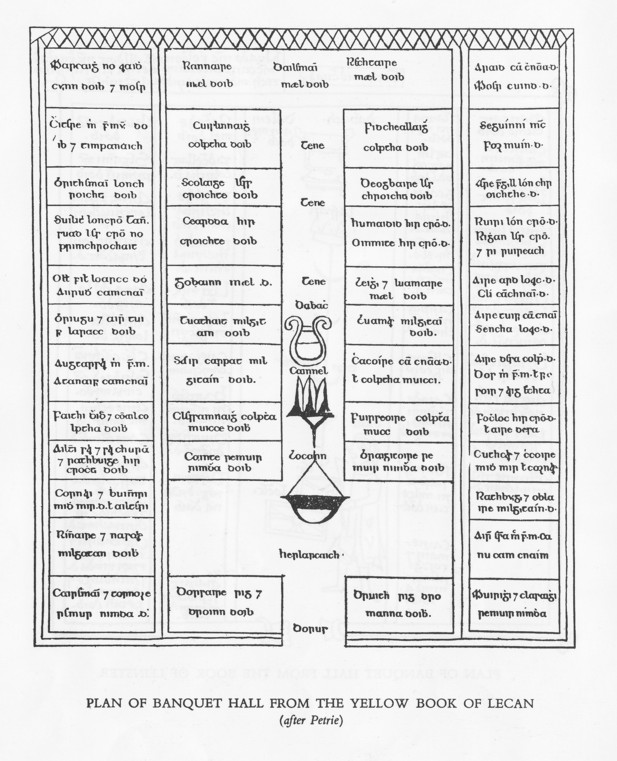

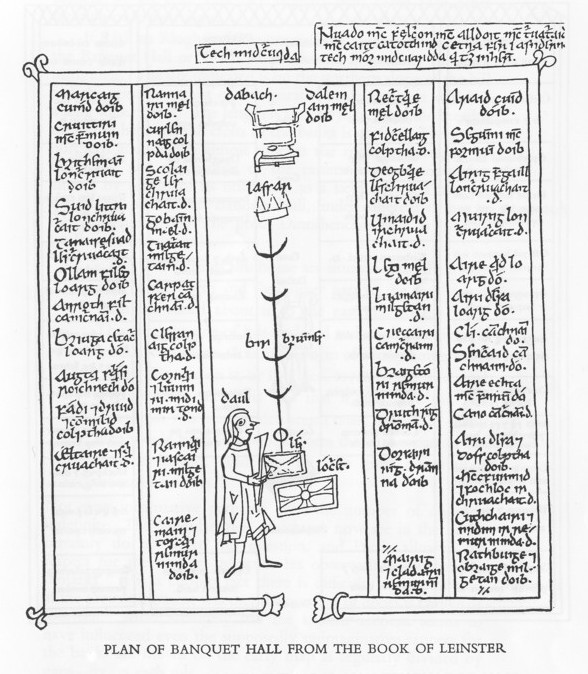

These plans from the 15th-century Yellow Book of Lecan and the 12th-century Book of Leinster show the seating arrangements for the guests according to rank and profession.